The Working Student Exchange: Are We Eating Our Young?

By Ashley Harvey

The working student arrangement is a fixture in busy competition and training barns across the country in eventing, hunters, dressage and show jumping alike. It’s considered a stepping stone for students that want to get in the weeds of the sport to develop their skills, often with the goal of becoming more competitive or a professional in the industry.

The relationship is a symbiotic one. A professional rider and a student agree on an exchange of services — the student provides a professional rider or trainer with barn labor and grooming, and in return the student gets training from the professional.

“It gives someone an understanding of the business behind the competition ring,” said Eiren Crawford, who spent years as a working student for various top riders including Ingrid Klimke and Lars Petersen, and is now the head trainer at All Points Dressage in Baltimore, Md. “In dressage, the goal is the six minutes in a little white rectangle, but that’s six minutes of a 24-hour day. The rest of the time, you’ve got to know how hard it’s going to be, what it’s like when things go badly, and how to manage horses, clients, a property and a business.”

[emaillocker id=”11445″]

Grand Prix dressage rider Lauren Chumley built the foundation of her professional career over many years as a working student.

“I was a working student for many, many years before I was hired as an assistant trainer which, after years, led to the ability to start my own business,” said Lauren of Pittstown, N.J. “I learned so much from my years as a working student. I learned much more than just riding skills: barn operation, sport horse care and management, teamwork, and client interaction. I also learned how to be a top show groom and everything that is involved in producing show horses. There is absolutely no way I would have been able to function in a professional capacity without the experience gained from my years as a working student.”

No Set Standard

This important step of education is especially attractive to riders that may not have the financial means to pay for training opportunities. In a survey conducted by Heels Down of over 300 former working students, 42% of respondents reported that their decision to become a working student was at least partly financial.

Remember that anyone can take to social media.

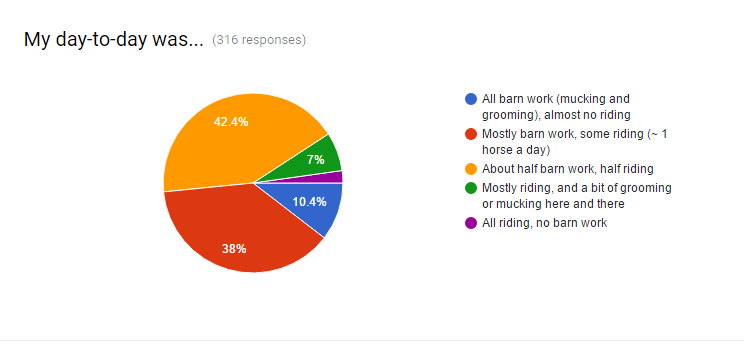

In terms of the value received on the student’s end, one arrangement can be vastly different from the next. While typically a six-day work week from mornings to evenings is required, the ratio of barn work to riding varied in survey participants.

Almost all (91%) reported that lessons were received as part of the arrangement, 36% received housing during their time as a working student, 33% received board for one horse, and about a quarter (27%) received a small salary or stipend.

Almost all (91%) reported that lessons were received as part of the arrangement, 36% received housing during their time as a working student, 33% received board for one horse, and about a quarter (27%) received a small salary or stipend.

Busy professionals are often at the mercy of finding committed working students. Daily operations rely on more than their one set of hands, but paying full-price for staff becomes cost-prohibitive. Many professionals ask for a six-month commitment from a working student, because there isn’t always a line out the door of young athletes that want to work long days at a physically exhausting job for no (or almost no) pay, even if they’re greatly enhancing their skill in the sport.

“Many young people that contact me about a potential working student position simply don’t want to do that much work,” said Lauren. “The horse industry knows no hours and this will never be a 9 a.m. – 5 p.m. job. They’re up early and sometimes out late working. Sometimes our days are twelve hours long.”

Burnout or Natural Selection?

If the working student experience is crucial to developing riders and horsemen, it’s imperative that the student’s level of ability and ambition can be accommodated by the trainer. There’s a limiting factor at play, however, because there aren’t enough positions with top people and many trainers don’t readily send their students on up the ranks once they’ve outgrown their skillset.

“It’s understandable, because they don’t want to give up that income and they probably feel committed to that student,” said Eiren. “But if the working student format is going to be a good pipeline for developing professionals in the industry, it’s important to get them into barns that can develop them, even if they’re not on developing rider or high performance training lists.”

Burnout is another factor that whittles down the number of successful riders that the arrangement produces. For Eiren, there’s a bit of natural selection at work, but the unregulated nature of the job means that workplace abuse often goes under the rug.

“It’s kind of a weeding out process,” she said. “On the other hand, there are plenty of professionals who blatantly take advantage of their working students. I worked at one barn for a year and a half, and during that time, 18 other working students came and went – people were just burning out so quickly. But now, looking back, I feel it was 100% worth it.”

Not every former working student feels this way. Sarah (last name withheld) held a working student position with an eventing trainer for six months, and admits she would never do it again. She said the situation set her back in her riding career.

“It was a classic situation of ‘trainer sees young, excited, willing person and takes advantage of them,’” she said, explaining that she rarely received the lessons she was promised, worked 7-day work weeks frequently, and was denied board for her horse, which she had been promised.

“I feel I became a worse rider. I rode a horse I had no business being put on that destroyed my confidence,” she said. “I learned a very valuable lesson and I now know the negative sides of the horse world, which I was never exposed to before.”

The Bigger Picture

If you plucked this scenario from the horse world and placed it in a larger societal arena, or perhaps another sport, “it would never fly,” said lawyer and owner of JurisEquine, Jessica Sutcliffe. There doesn’t seem to be a similar structure in other sports, and the situation isn’t clearly defined in many cases.

You’ve got to know how hard it’s going to be, what it’s like when things go badly, and how to manage horses.

Jessica strongly advises that a thorough, detailed contract is negotiated and signed before the stint, both to protect the student and the professional.

“The first thing I would tell a professional is to get a contract together because it protects both parties,” Jessica explained. “Lay out the hours of the working student, what duties will be expected, and exactly what they will receive in exchange. Get everything in writing.”

Without a contract, if the terms aren’t held up by either party, there isn’t much that can be done except walking away from the situation. However, the horse world is a small one, and this can sometimes come at the cost of reputation.

“Remember that anyone can take to social media,” said Jessica. “That’s something that can follow you even outside of the horse world.”

Eiren says that when considering a working student position, it should come down to at least one of these three key factors:

“One is money, but this is almost never a lucrative gig. Two is education, and three is fun,” she said. “There’s got to be one of those three things, but you’re not going to get all three. You should be getting an education, or you better be having fun.”